Belgium

“” Another Armenia, Belgium ... the weak innocents who always seem to be located on a natural invasion route.

|

| —Captain James T. Kirk, "Errand of Mercy."[1] |

“”On Earth, Belgium refers to a small country. Throughout the rest of the galaxy, Belgium is the most unspeakably rude word there is.

|

| —BBC explainer on The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.[2] |

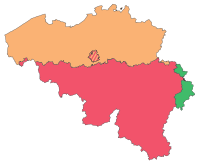

The Kingdom of Belgium, also known as Germany's Speed Bump, is a small country located in the Benelux region of Europe. It's split mainly between two major linguistic groups: the Dutch-speaking Flemish Community, which constitutes about 60 percent of the population, and the French-speaking Community, which comprises about 40 percent of all Belgians. There's also a small German population located on the eastern fringes. Belgium's resulting cultural diversity means that a headache-inducingly complex governance system is in place to ensure representation for everyone. Belgium is also notable for hosting the headquarters of both NATO and the European Union. Its capital and largest city is Brussels. Regarding the population's religion, 54% are Catholic, 3% are Protestant, and 31% are atheist or agnostic.[3] Its government is a constitutional monarchy ruled by a branch of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

During the Middle Ages, Belgium was one of the less shitty parts of Europe, thanks to its status as a trade hub. Through royal marriages, Belgium, alongside the Netherlands, became a holding of Austria and then Spain. It thus played a major role in the Hapsburg dynasty's struggles in Europe, especially against France, earning it the nickname "The Battlefield of Europe".[4] After the Protestant Reformation, Spanish religious persecution of non-Catholics in the Netherlands incited them to revolt in the Eighty Years War, beginning in 1568. Due to mainly being Catholic, Belgium stayed with the Hapsburgs after the Dutch got their independence. France conquered Belgium from Austria during the French Revolutionary Wars, and the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814 saw Belgium be handed off to the Netherlands.

Due to poor treatment at the hands of the Dutch monarchy, Belgium revolted in the 1830 Belgian Revolution, gaining success with the support of France. It became a colonial power involved in the Scramble for Africa, and its evil king Leopold II was responsible for the myriad atrocities inflicted upon the Belgian Congo. Even after Leopold II, the Congo remained an oppressed and mistreated Belgian colony. In World War I, the German Empire invaded Belgium to take a shortcut to Paris, and the Germans inflicted atrocities upon the Belgians, costing many lives. In World War II, Germany invaded Belgium for the same reason, committing atrocities.

After the war, Belgium attempted to maintain its colonial empire despite the opposite global trend. This resulted in the 1960 Congo Crisis, inflaming ethnic problems in the region and setting the stage for further strife in Africa.[5] Belgium also had problems closer to home as economic inequality between the Flemish and the French speakers caused political crises and forced the creation of Belgium's current federal government structure. Today, though, Belgium is a remarkably developed country with high standards of living, healthcare, and education.

History[edit]

The Belgae[edit]

“”All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in our Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws... Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest, because they are furthest from the civilization and refinement of [our] Province, and merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind; and they are the nearest to the Germans, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war.

|

| —Julius Caesar, The Gallic War.[6] |

Modern Belgium takes its name from the Belgae tribe who lived in the region that the Roman Empire knew as Gaul. During his campaigns, Julius Caesar applied the term "Belgium" to the region where they lived. Caesar's campaigns were called the Gallic Wars, and they saw the Belgae form a coalition with other Gallic tribes to resist Roman imperialism.[7] At least some of them crossed into Great Britain, where they established some petty kingdoms in the south.[8]

After the conquest by Caesar in 50 BCE, much of northern France became the Roman province of Gallia Belgica, which served as a militarized frontier against the various Germanic tribes.[9] The later Roman period saw Christianity begin to spread among the people of Belgium. In the 4th century CE, Saint Servatius of Tongeren became one of the first known Christian bishops in the Low Countries, and he played a major role in converting the region.[10] He died in Maastricht, traditionally in 384, and he soon became the subject of legends and tales of miracles.[11] His remains were buried at Maastricht and became relics that attract Catholic pilgrimage.

When the Western Roman Empire's government collapsed, Belgium came under intense assault from Germanic tribes, eventually culminating in the end of ancient civilization across the region.

Middle Ages[edit]

Belgium endured a turbulent few centuries being tossed between the Franks and the Germans. It finally became part of the empire of Charlemagne in 768 CE, and Charlemagne did much to encourage trade along Belgium's rivers to boost its prosperity.[12] After Charlemagne's death, his empire was destroyed by disputes between his sons. Unlike modern monarchies like the UK, many Medieval monarchies chose to partition their holdings to ensure that all sons of the old king got a piece of the pie. Thus, Belgium and the empire as a whole got split between Charlemagne's heirs.

The Flemish part went to France too, which they weren't too happy about. Flemish noble Baldwin Iron Arm decided to prove his independence by carrying off and marrying one of the French king's daughters.[13] His most pressing threat, though, came from outside. It was the 800s CE, and the Vikings had become a persistent and perpetual pestilence across the shores of Northern Europe. Baldwin countered them by building fortress cities to protect Belgium's rivers, first Ghent in 867 and followed by Bruges and Ypres.

The Norse raids eventually fell off, allowing trade to grow. With its extensive coastline and rivers, Flanders had a golden era, as its cities became rich by buying wool from England and weaving it into clothing.[13] Flemish cities became way more powerful than the French monarchy had counted on, and their cultural differences from the French made them seek further autonomy. However, France wasn't about to let such a lucrative source of wealth and power dissolve its loyalty to the throne. In 1297, King Philip IV attacked the County of Flanders, his own vassal, to force it to reintegrate with his realm.[14] Flanders eventually collapsed beneath the greater strength of France, but at a high cost for the French.

England, though, had made bank by selling wool to the Flemish, and they weren't pleased with this outcome. The English banned wool sales to Flanders so long as the French were in control.[13] In 1337, England and France went to war over dynastic issues (long story, monarchy is stupid), resulting in the Hundred Years War, while Flanders used the chaos to regain its independence.

Burgundian era[edit]

In the bloody horror of the Hundred Years' War, the French House of Valois put one of its members onto the seat of the French subject Duchy of Burgundy. This backfired because the Valois in question, Charles the Bold, was an ambitious noble who married Margaret of Flanders, daughter of the Count Louis II of Flanders, and thus integrated that rich region into his own holdings.[15] Burgundy went from being a region in eastern France to a kingdom in its own right. By 1435, Burgundy's independence became pretty much official under Philip the Good, as he lost interest in internal French affairs and focused on territorial expansion.

Philip the Good established Brussels as his capital and ordered the palace at Coudenberg to be expanded into a proper royal headquarters (which sadly burned down in the 1700s).[16] Philip's reign was one of extravagance. This was when much of modern Belgian cuisine started to come into shape, the arts received patronage from the monarchy, and when knights of Burgundy wore huge golden neckties.[17] The Middle Ages were sure shitty for Europeans, but Belgium was one of the least shitty places. In fact, many Belgians still regard the 15th century as one of their golden ages.[18] Meanwhile, the English, French, and Germans were killing each other in shit.

Unfortunately, the Burgundian era contained the seeds of later problems. Under the Burgundians, the French-speaking Wallonia region was favored over Flanders, a situation that persisted for much of Belgium's history.[19]

The Burgundian dream ended when Philip the Good's not-so-Good son Charles took the throne. He got into a dumb war with the Holy Roman Empire and died at the Battle of Nancy in 1477.[20] With no male heir, his daughter Marie inherited Burgundy and promptly became the most desirable bachelorette in Western Europe.[17] After all, whoever married her would have their children inherit an entire kingdom. The King of France tried to entice Marie into marrying his son Charles VIII, but the twenty-year-old duchess wasn't keen on hooking up with a six-year-old.[21] Thus, she chose to marry Archduke Maximilian of Austria, heir to the Holy Roman Empire and the soon-to-be head of the powerful Hapsburg dynasty.[22] It also helped that he wasn't a six-year-old.

The French were enraged at this perceived slight. They were especially pissed since Burgundy was originally a French vassal, and the marriage had turned it into an Austrian holding. This dispute escalated into war almost immediately, beginning a bloodbath that lasted until 1493 with a settlement that allowed France to retake most of Burgundy but cede the Low Countries to Austria.[23]

Hapsburg rule[edit]

The Hapsburg acquisition of the Low Countries had a tremendous impact on Europe. On the political front, it set the stage for further growth in Hapsburg power, most notably when they put themselves onto the throne of Spain and thus took control of its vast colonial empire. The Hapsburgs adopted many Belgian customs through their union with Burgundy on the cultural front. The sophisticated royal court lives and traditions of the Hapsburgs, which helped create a ruler cult and ensure loyalty from vassals, were modeled on the Burgundian ducal court.[23] Archduke Maximilian was also a brilliant propagandist, and the political success in the Low Countries expanded his influence and wealth. He crafted a romantic story about himself and his courtship of Marie, and he used art and writing to portray himself as the "last knight", a follower of the dying art of chivalry.[24]

It didn't take long for the people of Belgium to start chafing at Hapsburg rule. The Hapsburgs already had to deal with the Holy Roman Empire, an agglomeration of rebellious and mostly-independent states, so they weren't about to put up with the same shit in the Low Countries. Thus, Charles V promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, which pissed off everyone in the Low Countries by yanking much of their autonomy away and grouping them into one mega-polity under Austrian rule.[25] The Hapsburgs alienated people even further by taking land in the Low Countries, giving it out to bishops, and then passing strict laws against heresy.[26]

Eighty Years War[edit]

The Hapsburg line eventually partitioned the dynasty's holdings between Austria and Spain. Unfortunately for the Low Countries, they were passed to Philip II of Spain, a zealous Catholic and very religious intolerant.[27] This suppression of different religions was bad since the Protestant Reformation had become very influential there. Persecution of Protestants in the region grew most severe after the 1550 "Edict of Blood", which ordered that anyone following the Protestant movement would be put to death.[28] About 1,300 people were executed over matters of religion between 1523 and 1566.[29]

Protestantism was most entrenched in the Dutch provinces, and they revolted and began a war in 1567 under the leadership of William of Orange, a Dutch noble.[30] Although many of the Flemish and most French speakers of Belgium remained Catholic and mostly loyal, this didn't spare Belgium from the horrors of the war. The brutal Duke of Alba used the Army of Flanders to begin a reign of terror across the Low Countries by executing and brutalizing anyone he suspected of disloyalty or heresy.[31]

In 1576, the Army of Flanders carried out the greatest massacre on Belgian soil in its history. The army mutinied due to the Spanish failure to pay them and then attacked the rich city of Antwerp in the hopes of getting paid via looting. They broke into the city and murdered some 18,000 residents while burning much of it down.[32] At this point, even Belgian Catholics lost their loyalty to the Spanish crown. Spain spent over a decade painstakingly regaining control of rebellious Belgian cities like Maastricht, Bruges, and Ghent.[33] During this process, Antwerp got fucked yet again when the Spanish took it in 1585, causing most of the city's population to flee north in terror.[34] The refugees included most of the city's merchant class, meaning its economic strength was destroyed for decades afterward.

Under new command, the Spanish did their best to limit the damage of their sieges and promise conciliatory terms to the Belgians, with the end effect being that they gradually regained their tolerance for the Spanish.[35] It also helped that many of the Protestants had fled to the Netherlands. Thus, after many decades of war, most of Belgium remained a Spanish holding.

Early Modern battleground[edit]

The end of the Eighty Years War wasn't the end of Belgium's misery in the Early Modern era. The Eighty Years' War occurred in the same context as the Thirty Years' War, which saw France rise to the status of a European superpower thanks to its large population and economic base. The French hated the Hapsburgs due to territorial disputes and a long history of war, and Spanish-ruled Belgium just happened to be across the border. It should be no surprise then that Belgium got invaded a lot. Like, a lot.

The Spanish did have help in resisting the French, though, as the Netherlands didn't want France on their borders either, and England also hated the French.[36] Belgium became the stomping grounds for four major powers basically nonstop for many decades. Perhaps most destructive for Belgium was the War of the League of Augsburg that started in 1688, in which Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, England, the Netherlands, Portugal, and even Sweden fought the French on Belgian soil.[37] In 1695, the French destroyed about a third of Brussels with artillery to gain the upper hand over the League's armies.[38] The attempt failed, but it did nicely fuck over the Belgians.

Almost right after the League war ended, another began after Spanish ruler Charles II died without an heir. After more years of destructive war, the Hapsburg line was extinct in Spain, and Belgium was passed back to Austria.[39] The Austrians had little interest in Belgium since it was so far away and had proven itself to be a colossal pain in the ass to protect from various other European powers. Thus, Belgium largely got to run its own affairs so long as it paid tax to the Austrians. This contributed to a gradually growing sense of nationalism and identity, as Belgium clearly wasn't Austrian, wasn't too happy with the French, and had chosen not to be Dutch.[36]

Revolutionary era[edit]

In the 1780s, Emperor Joseph II started attempting to reassert control over Belgium, which didn't fly over well. These attempts were ultimately doomed by the progress of history, as in 1789, Austria became preoccupied with the much more pressing matter of the French Revolution and its threats to Hapsburg princess Marie Antoinette, who also happened to be the Queen of France. Centered around Ghent, the Belgians followed the French example and rose up in the Brabant Revolution, hoping to declare independence as a republic.[40] However, the movement's leaders were divided on the issue of how progressive their policies should be, and they were unable to organize sufficiently to prevent themselves from being crushed by Austrian armies less than a year later.

That wasn't the end of the revolutions in Belgium, though. If the Belgians couldn't join the French Revolution, then the French Revolution would join them. In 1795, the revolutionary armies of France stormed Belgium while fighting against Austria and the coalitions. This ultimately wasn't a great outcome for the Belgians. While the French implemented some good reforms like equal legal rights and the abolition of class distinctions, they viewed Belgium as an occupied territory to be heavily taxed and used as a source for conscripted soldiers.[41] Belgium had a popular government, but it wasn't very popular. The French made themselves unpopular by oppressing Catholics for a while, as religion was seen as contrary to the revolutionary Enlightenment ideals. In 1798, Belgium rose up in the Peasants' War to resist conscription.[42]

Under Napoleon Bonaparte, though, French rule in Belgium became noticeably better, with more of an emphasis on building industry and less on destroying churches.[43]

Dutch rule[edit]

After Napoleon's downfall in 1814, the triumphant coalition decided to compensate the Dutch for their participation by giving them control of Belgium. This led to the so-called "United Kingdom of the Netherlands", which wasn't very united. The forced union pissed off much of the Belgian population since the Catholics didn't want to be ruled by a Protestant king, the nationalists didn't want to be ruled by a Dutch king, and liberals didn't want to be ruled by a king at all.[44] This crisis was briefly paused in 1815 when Belgium became a battleground again when Napoleon tried to come back and then fought the Battle of Waterloo on Belgian soil.[45]

Back to regularly scheduled programming, the Dutch tried to impose the use of their language on the French regions and encroach on Catholic traditions.[46] The people weren't happy about that. The Belgians were also underrepresented in Dutch institutions. They didn't like that much either. The Dutch refusal to allow freedom of expression alienated the liberals, while the Dutch hostility towards Catholicism alienated the conservatives.[47] Deciding that they had a common enemy, the political factions in Belgium set aside their differences to oppose the Dutch.

Belgian Revolution[edit]

In 1830, the various grievances against the Dutch culminated in an uprising in Brussels. Dutch king William I sent in his troops, but they failed to take the city despite determined local resistance from volunteers.[48] Shortly after, the movement became national, and Belgium declared independence.

Post-Napoleon, the great powers of Europe were a bit shy about jumping into wars all willy-nilly, and the Belgian Revolution presented an international crisis they hoped to resolve with diplomacy. Hence the London Conference, where Austria, Britain, France, Prussia, and Russia considered the possibility of partitioning Belgium along language lines but eventually followed the will of the Belgian people in recognizing their independence.[49] Belgium's two most vocal advocates, the UK and France, saw themselves as guarantors of Belgian independence. The British were especially happy with Belgium since they took Leopold I of House Saxe-Coburg-Gotha as their constitutional monarch, advancing their dynastic aims.[50] In early 1831, Belgium elected a National Congress and adopted a pretty liberal constitution for the time.[48]

Still butthurt over the loss of Belgium, the Netherlands tried an invasion one more time in 1831. The campaign was a miserable failure since the Belgians asked the French for help, and the Dutch chose to back down rather than get fucked by France.[51] The Dutch were still pissed off until the Treaty of London was signed in 1839, which finalized their borders and mandated that Belgium would forever be a neutral country.[52] The neutrality was essential since all signatories, including the UK, France, and the future German Empire, promised to use military force to protect that neutrality should it ever be violated. This is foreshadowing.

Kingdom and colonial empire[edit]

“”Primary education includes by necessity the teaching of religion and morality... The instruction of religion and morality is placed under the direction of the officials of the religious faith that is professed by the majority of pupils at the school.

|

| —Article 6 of the Education Act of 1842.[53] |

Belgium, formerly considered a backwater of the Low Countries, launched itself into international prominence thanks to becoming the second country to fully embrace the impacts of the Industrial Revolution. Factories developed rapidly in an open economy while the government invested in education and established good export markets for their manufactured goods.[54] Belgium especially benefited from its abundance of coal and rapidly developing textiles industry.

Politically, Belgium was torn between the conservative Catholic Party and the Liberal Party, a conflict that came to a head in 1879 over the issue of religious teaching in schools.[55] Liberal attempts at secularizing schools were foiled due to boycotts from Catholic clergy, who were largely responsible for school education at the time. Shortly after that, a long period of economic decline set in, setting the stage for various strikes from the working class that often escalated into bloody violence.[56] It's no surprise then that socialism started to take root in Belgium.

Meanwhile, Belgium's second king Leopold II began focusing on his colonial ambitions. During the Scramble for Africa, Leopold II got the Belgian Congo recognized as his personal property in 1885 (meaning that it was owned not by Belgium™ but by Leopold as an individual because everyone wanted the Congo, and this way, its resources could be sold to everyone). Under his rule, the Congo became a brutal slave labor regime focused on producing rubber to fuel the growth of the automobile industry, and conditions were so bad that between 8 and 10 million people died.[57] Native laborers were given quotas by their overlords, and failure to meet them would be met with arson, rape, whippings, and massacres.[58] The quotas themselves were insane, motivated by nothing but sheer profit. Leopold also hired mercenaries to enforce these demands, infamously mandating that they sever the hands of anyone they killed to prove that they weren't wasting bullets on hunting or sport.[59] Government-issued guns are only for shooting people, y'see. Of course, the undisciplined mercenaries couldn't help themselves, so to cover it up, they just raided villages and severed hands from living people.[60]

Impressively, even other colonial powers were horrified by this, so eventually, in the name of PR, the Belgian government seized the territory from King Leopold and established the Belgian Congo as a nationally-owned colony.[61] THowever, things didn't get much better as slave labor continued. Belgium also started opening human zoos in 1897 to showcase the African natives as animals, and these hideous exhibitions remained a thing until 1958.[62] Visitors would throw peanuts, and the Congolese would die from neglect and preventable diseases. Just awful.

World War I[edit]

Due to decades of diplomatic stupidity, the German Empire found itself at war on two fronts, against Russia and France, during World War I, with only the militarily weak empire of Austria-Hungary to help them out. The Germans had realized for a long time that this would be the case, and the plan they drew up to deal with it called for a rapid invasion of Belgium to take a shortcut to Paris and thus knock France out of the war early.[63] German general Helmuth von Moltke weakened the already tentative plan by taking troops away from the Belgian front to strengthen a doomed attack along the French border further south.[64] Stupid.

The Germans invaded Belgium in August 1914, effectively ripping up and taking a shit all over the 1839 Treaty of London in which they had pledged to defend Belgian neutrality. The British were highly offended by the German treaty violation, especially when Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg laughed the treaty off as a "scrap of paper".[65] This was one of the factors that prompted the UK's entry into the war.

For Belgium, this additional ally came much too late. Despite some initial fuckups (like marching parade-style into machine-gun fire[66]), the Germans managed to take Brussels by August 20th.[67] Still, Belgian resistance was determined. The opening engagement, the Battle of Liège, delayed the German invasion of France by almost a week and thus played a major part in foiling the German war plan.[68]

What followed was the infamous "Rape of Belgium". German soldiers acted with brutality against Belgian civilians during the occupation, shooting civilians, burning villages, and murdering priests.[69] The Germans were frustrated by the determined Belgian resistance, and they often took it out on the normal people of Belgium, sometimes after baselessly accusing them of being covert snipers.[70] It's estimated that about 6,000 Belgians were murdered outright, while more than 17,000 died during the subsequent occupation.[71]

The Germans also wanted to stop Belgians from fleeing into the neutral Netherlands, so they built and guarded a 2,000-volt electric fence complex across the border, which is estimated to have led to the deaths of at least 1,000 people.[72] It's now called the "Wire of Death."[73] The Belgian economy was further destroyed as the Germans looted industrial equipment and later started using Belgian civilians as forced labor.[74]

Many of the great killing grounds of WWI were in Belgium, as the Entente allies tried to liberate it from the Germans with little success while the Belgians tried to hold out around Antwerp. These battles included the Siege of Antwerp, the Battle of the Yser, the Battles of the Ypres, and the Battle of Mons.[75]

Interwar period[edit]

Belgium had the unenviable task of recovering its entire country from a prolonged German occupation and its usage as the site of many of the Great War's bloodiest battlefields. Aside from the direct damages as a result of warfare, industry nearly came to a standstill under the German occupation, causing mass unemployment.[76] Belgium had assumed that reparations from Germany would help them pay for the effort, but Germany's wrecked economy made that hope impossible. Reconstruction wasn't complete until 1924, and Belgium only managed that by going into heavy debt.[76]

On the other hand, the postwar settlement abolished Belgium's historical requirement for neutrality and saw it gain a small amount of territory from the German Empire.[77] The government also appeased people by implementing democratic reforms like universal adult male suffrage, which saw the Liberal and Socialist parties start to gain significant political influence at the expense of the Catholic conservatives. Even the Catholic Party saw an internal shift from religious moralism toward Christian democracy.

Belgium also got fucked by the Great Depression, as its insistence on keeping the gold standard left the franc seriously overvalued as the pound sterling and dollar fell, resulting in falling exports and profits.[77] It took until 1935 for Belgium to give up on gold. Poor economic conditions contributed to political extremism, most notably under the fascist Rexist Party of Léon Degrelle, which received funding from Benito Mussolini.[78] Rexist influence in politics greatly weakened the Belgian government's ability to cope with crises as it took up seats in parliament just to obstruct everything. It argued for Catholic dominance, but hilariously, the chief Catholic official in Belgium, Cardinal van Roey, denounced the party as a danger to the church.[79]

World War II[edit]

Despite hoping to be neutral again, Belgium became forcibly involved in the Second World War when Nazi Germany invaded it in May 1940 on the way to France. The Allies tried to halt the German army in Belgium, only to have a German armored column smash through the Ardennes Forest and encircle much of the Allied force in Belgium and northern France.[80] An admittedly masterful campaign, the Eighteen Days in Belgium doomed France and Belgium and forced the UK to beat a fighting retreat to the French coastal city of Dunkirk to evacuate from the European Continent. Without consulting his government, Leopold III surrendered on behalf of Belgium and chose to remain in the country as effectively a captive.[81] When advisors and family members asked him to form a government-in-exile, 'Lil Leo refused and declared that the Allied cause was lost. Fucking quitter.

The civilian government basically told Leopold III, "fuck you", and formed an exile government without him, and relations between the king and his government were initially quite hostile. The exile government even went so far as to invoke the constitution to declare him unfit to reign because he was under the influence of foreign occupiers.[82]

Belgium was ruled by German military administration officers who used their position to tax Belgium roughly two-thirds of its economy to support the German war effort.[83] Belgium's economy sank again, and food shortages became inescapable under strict rationing.[84] Hundreds of thousands of Belgians were conscripted by the Germans to work as forced labor in war production factories.[85] Belgian prisoners of war were also shipped into Germany to work in forced labor camps.

Belgian resistance was decentralized and fairly weak, and most of its activities focused on small things like helping downed Allied airmen escape.[86] Belgians also helped Jews escape from Nazi persecution and the Holocaust. As the war started going south for the Germans, their conduct towards Belgian civilians escalated in brutality. War crimes against Belgians and Allied forces in Belgium included the Courcelles massacre (20 Belgian civilians killed).[87] and the Malmedy massacre (84 American POWs and about 100 Belgians killed)[88][89]

Meanwhile, the long-oppressed Belgian Congo proved instrumental to the Allied war effort by providing many soldiers and raw materials for industrial production.[90] The Congo remained loyal to the Belgian government-in-exile. Sadly, white Belgian officers ignored the contributions of the black Africans, who kept them racially segregated and ensured that blacks could never serve as officers.[91]

Belgium was liberated by the Allies between September 1944 and February 1945, considered a joyous occasion by those Belgians who weren't collaborationist pieces of shit.[92]

On the plus side, being on the receiving end of imperialism for once made them realize that their treatment of the Congolese might not be all that ethical.

Political crises[edit]

The Royal Question[edit]

Immediately after liberation, Belgium faced the pressing issue of what to do about their king, Leopold III. He had chosen to surrender to the Germans without consulting the civilian government, and the government had declared him unfit to continue ruling Belgium. The king's popularity also plummeted further when it came out that he had tried to get an audience with Adolf Hitler himself while still stating that the Nazis would win.[93] After the king was declared unfit to reign, his reclusive brother, Prince Charles, Count of Flanders, became regent. Leopold's position was even further complicated when the British government expressed contempt for him and used diplomatic pressure to keep him from the throne.[94]

Prince Charles proved to be a much better ruler than Leopold III. He used his influence to push for more democratic reforms in Belgium, like women's suffrage and a social welfare system.[95] Meanwhile, Leopold was stuck in exile in Austria, where he had been deported by the Germans. Leopold had stupidly delayed his return to Belgium, and under a new coalition government led by the Liberal and Socialist parties, he was no longer allowed to. This situation remained until 1949 when elections brought the conservatives back into government. They arranged for a referendum in 1950 on whether Leopold III should become king once more.

The referendum ultimately passed with 58% of the vote, and Leopold III returned to Belgium secretly and under heavy guard.[95] His arrival prompted workers' strikes and civil unrest across Belgium, resulting in three young men being shot by police.[95] The political crisis this caused finally convinced the king to abdicate in favor of his son Baudouin.

Congo's independence and war[edit]

Since Belgium had never really intended to take control of the Congo, only having been forced to do so after Leopold II caused a scandal by being a brutal son of a fuck, the Belgian authorities were shockingly neglectful of the colony. For the entirety of Belgian rule, the Congolese were denied infrastructure and education because the Belgians just never wanted to put effort into those things.[96] The Belgians were still reluctant to let it go, however, since, despite the tiny investment, the colony was a source of cash. As late as 1959, Belgian officials dismissed any talk of independence for the Congo as wildly unrealistic fantasies, and their plan was to grant the Congo limited self-governance thirty years from then.[97] That wasn't gonna fly when the Congo was surrounded by newly-independent African nations, which even the Belgian police state couldn't hide from the Congolese.

Rioting in the Congo's capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) combined with violent altercations between Belgian forces and the Congolese convinced Belgium that the colony wasn't worth it anymore.[98] Not even a year, Belgium simply dumped the Congo in 1960 with minimal preparation or notice and scuttled back to Europe. This was to have disastrous consequences.

Having been dumped aside with no care, the Congo promptly melted into civil war, and various factions started attacking whites. In response, the Belgians dispatched troops briefly before being asked to withdraw by the Congolese government.[99] Then, dominated by Belgian business interests, the mineral-rich Katanga province under the leadership of Moïse Kapenda Tshombe attempted to secede with Belgian support. Meanwhile, the US and the UN increasingly desperately tried to keep the country together to prevent a crisis that would create an opening for the Soviet Union in the Cold War.[100] The Congolese government gradually regained control of its territory, but political violence and instability remained constant.

Flemish movement[edit]

Political problems in Belgium soon resumed after the crises over the king and the Congo. Growing economic disparities between Flanders and Wallonia created dissatisfaction with Belgium's unitary government system. Long underserved compared to Wallonia since the Burgundian era, the Flemish were finally sick of being neglected. The French speakers feared that the more populous Flemish would dominate the Belgian state, and tensions between the two groups caused workers' strikes and political instability.[101]

Beginning in 1969, a slow transition toward federal rule began in response to the political problems between the French speakers and Dutch speakers. The parliament accorded cultural autonomy to the Flemish and Walloon regions in 1971, and in 1980 a revision of the constitution allowed for the creation of an independent administration within each region.[102] The regions eventually gained the right to manage their economic and educational affairs. Brussels, a bilingual metropolis, became its own independent region in 1989 alongside an agreement that formally made Belgium a federal state.[102]

Modern Belgium[edit]

After World War II, Belgium increased its ties with the rest of the world in the hopes that it wouldn't have to be stomped on by invaders anymore. In 1949, Belgium became a founding member of NATO, and it still places great importance on the Article 5 promise of collective defense.[103] After all, Belgium doesn't want to get stomped on anymore. Belgium also helped form the Benelux Union alongside its neighbors, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, to foster cooperation on whatever these little countries wanted to do.[104]

Belgium also became a founding member of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 and the European Economic Community in 1957. The EEC evolved into the European Union, and Belgium's capital became the so-called "capital of Europe".[105]

Government and politics[edit]

The politics of Belgium takes place in a framework of a federal, parliamentary, representative democratic, and constitutional monarchy.[106] And we're sorry, but making Belgian politics sound simple is nigh impossible.

Federal[edit]

The Belgian Federal Parliament is the bicameral legislature of Belgium. Electoral districts in Belgium are divided along linguistic lines, and the Belgian Senate is elected by the community and regional parliaments (we'll get there).[107] Since the Senate is much less democratic, it has fewer powers than the directly elected Chamber of Representatives. The Prime Minister of Belgium serves as the head of government for the country, and they are appointed by the king based upon the Chamber of Representatives majority party's recommendation.

The Belgian Chamber of Representatives election is based on a system of open-list proportional representation. Belgian elections are interesting since the state has a compulsory voting system, where adults 18 and over may face a moderate fine if they fail to vote.[108]

Monarchy[edit]

Belgium's head of state is officially its king. The current king is Philippe. His father, ex-king Albert II, spent more than a decade fighting paternity claims by Belgian artist Delphine Boël before being forced to admit that she is his illegitimate love-child after having it confirmed by a DNA test.[109] Even then, he only took the paternity test after a Belgian court threatened to fine him if he didn't.[110] Delphine Boël was understandably a bit sore over having been rejected for so many years by her father. Oof. She recently sued the monarchy for royal privileges and titles.[111]

Besides being a scandal machine, Belgium's monarchy serves a largely ceremonial role. Monarchs do not publicly discuss politics, and they do what the elected majority party asks.[112]

Federalism[edit]

Language has been a major political issue in Belgium for a long time due to centuries of disparity between the Flemish and the French speakers. In hopes of rectifying this, Belgium partitioned itself into several sub-national governments to ensure representation for everyone. This is a big part of why Belgian politics is such a fucking headache for outsiders to figure out.

Belgium has two types of federated entities: Regions and Communities. Communities are based on the dominant language in each part of Belgium. There are currently three: the French Community, which comprises all the residents of Wallonia and French-speaking inhabitants of Brussels; the Flemish Community, which comprises all the inhabitants of Flanders and Brussels-based Flemings; and the German Community, which comprises German-speakers in those little areas Belgium took from the German Empire after WWI.[113] Communities elect their own parliaments and governments, with broad authority to set forth legislation within their territory.

The Regions are decided on land rather than language, notably giving Brussels its own Region.[113] Regions also elect their own governments and specific authorities within their territory.

Unfortunately, Belgium's overlapping and divided polities have hampered the country's efforts at responding to COVID-19, mainly since health authority is spread over all levels of government, meaning that there are nine different health ministers.[114]

International organizations[edit]

Brussels hosts multiple international headquarters. Its Berlaymont building hosts the European Commission, which is the executive authority of the European Union and thus makes Brussels the effective capital of the EU.[115] There's a whole section of Brussels called the "European Quarter", which houses the many EU organizations headquartered in Brussels.[116] Perhaps most notable is the Espace Léopold parliament complex, which houses most activities of the European Parliament. Despite all of this, though, Brussels is emphatically not officially declared the capital of the EU, as that would create the official appearance of favoritism. Strasbourg and Luxembourg City also share competing claims to the title of "capital of Europe" since they also host many institutions of the EU.[117] Strasbourg even has another EU Parliament headquarters.

NATO is also headquartered out of Belgium, perhaps strange for such a United States-dominated alliance.[118] NATO has been located there since it was originally in Paris but was forced to leave after France abruptly quit the alliance in 1966.[119] NATO had to build a new facility since the original move had been conducted so hastily that they ended up in a crappy temporary office building. It stores some symbolic artifacts like chunks of the Berlin Wall and pieces of the Twin Towers from 9/11, the event which prompted the only activation of NATO collective defense.

Religion[edit]

Roman Catholicism is the majority religion in Belgium, but church attendance is quite low. By 2009, Sunday church attendance was 5% in Belgium, 3% in Brussels,[120] and 5.4% in Flanders. Church attendance in 2009 in Belgium was roughly half of the Sunday church attendance in 1998 (11% in 1998).[121] The ancient Catholic political party has become independent from the Catholic Church and has since been split with federalization. The Walloon party (cdH) now follows the ideology of democratic humanism. The Flemish party (Cd&v) still identifies itself as Christian-Democratic, though it doesn't care about big Catholic issues such as gay marriage.[122]

Islam is gaining ground quickly in Belgium. A 2008 estimate found[123] that 6% of the Belgian population, about 628,751, is Muslim (98% Sunni), while a 2011 estimate claims 1,000,000 inhabitants of Muslim background in the country.[124] Islamic extremism also accompanied this growth, however. Sharia4Belgium, the most Influential group, dissolved in 2012. On the other hand, Islamic extremism also became successfully politicized in the country starting from 2012 with the introduction of the Belgian political party Islam, which has the same goal as Sharia4Belgium, but which wants to achieve it by political means and currently has local representation.

According to the Eurobarometer Poll in 2010, 37% of Belgian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", whereas 31% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", and 27% said that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".[125]

Environmental issues[edit]

Due to population density, its location in the center of western Europe, and its history of being one of the oldest industrialized countries in Europe (industrialization in continental Europe more or less began in Belgium, and Wallonia is to Europe what the Rust Belt![]() is to the US), Belgium faces serious environmental problems, including "human activities: urbanization, dense transportation network, industry, extensive animal breeding and crop cultivation", as well as air and water pollution.[126] An environmental report which examined 122 countries in 2003 suggested that Belgian natural waters (rivers and groundwater) have the poorest water quality of any studied country.[127] This is despite Belgium being party to many international agreements regarding the environment.[126] Belgium has the lowest environmental rating of any EU country. However, it was only thirty-ninth out of 133 countries studied.[128]

is to the US), Belgium faces serious environmental problems, including "human activities: urbanization, dense transportation network, industry, extensive animal breeding and crop cultivation", as well as air and water pollution.[126] An environmental report which examined 122 countries in 2003 suggested that Belgian natural waters (rivers and groundwater) have the poorest water quality of any studied country.[127] This is despite Belgium being party to many international agreements regarding the environment.[126] Belgium has the lowest environmental rating of any EU country. However, it was only thirty-ninth out of 133 countries studied.[128]

Gallery[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Errand of Mercy Quotes. Trek Core.

- ↑ The Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy Guide. BBC.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Religion in Belgium.

- ↑ Haß, Torsten (17 February 2003). Review of Cook, Bernard: Belgium. A History. FH-Zeitung (journal of the Fachhochschule). ISBN 978-0-8204-5824-3

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Congo Crisis.

- ↑ Caesar, Julius; McDevitte, W. A.; Bohn, W. S., trans (1869). The Gallic Wars. New York: Harper. p. 9. ISBN 978-1604597622.

- ↑ Belgae. Britannica.

- ↑ Belgae. Encycopedia.com

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Gallia Belgica.

- ↑ Servatius of Tongeren. Livius.org

- ↑ Pilgrimage to Saint Servatius in Maastricht. Amsterdam Center for European Ethnology.

- ↑ Belgium: The Ancient Celts. Geographia.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Medieval Belgium. Geographia.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Franco-Flemish War.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Burgundian State.

- ↑ {{wpa|Coudenberg|}

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 When Belgium was called Burgundy. Brussels Time.

- ↑ The Burgundian Legacy – Belgium in the Fifteenth Century. Based in Belgium.

- ↑ Kramer, Johannes (1984). Zweisprachigkeit in den Benelux-ländern (in German). Buske Verlag. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-87118-597-7.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Nancy.

- ↑ Koenigsberger, H. G. (2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521803304. p. 49

- ↑ Kendall, Paul Murray (1971). Louis XI. W.W. Norton Co. Inc. ISBN 978-0393302608. p. 228

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Maximilian and the Burgundian inheritance. World of the Hapsburgs.

- ↑ Maximilian I: art in the service of politics. Hapsburger.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Pragmatic Sanction of 1549.

- ↑ State, Paul F. (2008). A Brief History of the Netherlands. Infobase Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 9781438108322.

- ↑ Belgium: Burgundian Period. Geographia.

- ↑ 1506-1555 The Netherlands under Charles V . Rijksmuseum

- ↑ Tracy, J.D. (2008), The Founding of the Dutch Republic: War, Finance, and Politics in Holland 1572–1588, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-920911-8 p. 66

- ↑ Parker, Geoffrey (1990). The Dutch Revolt (Revised ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140137125.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Army of Flanders.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Sack of Antwerp.

- ↑ Black, Jeremy (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492-1792, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780521470339.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Fall of Antwerp.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on History of Belgium § Dutch Revolt and 80 years war.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Belgium: The Battleground. Geographia.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Nine Years' War.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Bombardment of Brussels.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on War of the Spanish Succession.

- ↑ Brabant Revolution. Britannica.

- ↑ Kossmann, E.H. (1978). The Low Countries: 1780–1940. Oxford University Press. pp. 65–81, 101–2. ISBN 9780198221081.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Peasants' War (1798).

- ↑ Belgium: The New Kingdom. Geographia.

- ↑ [https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/150/Belgium-HISTORY-BACKGROUND.html Belgium: History and Background.

- ↑ Battle of Waterloo. National Army Museum.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on United Kingdom of the Netherlands § Regional tensions.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Unionism in Belgium.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Revolution and independence. Belgium.be.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on London Conference of 1830.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Leopold I of Belgium.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Ten Days' Campaign.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Treaty of London (1839).

- ↑ Galloy, Denise, Hayt, Franz (2006). La Belgique: des Tribus Gauloises à l'État Fédéral (5th ed.). Brussels: De Boeck. pp. 138–9. ISBN 978-2-8041-5098-3.

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on First School War.

- ↑ Marx and Engels on the Trade Unions. Edited with an introduction and notes, by Kenneth Lapides, Originally published, Praeger, New York, 1987, p. 69 ISBN 0-7178-0676-6

- ↑ 'King Leopold's Ghost': Genocide With Spin Control Kakutani, Michiko. New York Times. September 1, 1998

- ↑ Belgium's Heart of Darkness Stanley, Tim. History Today Volume 62 Issue 10. October 2012.

- ↑ Red Rubber: Atrocities in the Congo Free State in Confidential Print: Africa

- ↑ Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo (2007). The Congo: Plunder and Resistance. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-485-4.

- ↑ Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: the White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10449-2.

- ↑ Where 'Human Zoos' Once Stood, A Belgian Museum Now Faces Its Colonial Past. NPR.

- ↑ Schlieffen Plan. Britannica.

- ↑ Helmuth von Moltke. Britannica.

- ↑ Primary Documents - The Scrap of Paper, 4 August 1914.

- ↑ The World War One German invasion of Belgium… What happened next?. History is Now.

- ↑ The German Army Marches Through Brussels, 1914. Eyewitness to History.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Liège.

- ↑ The Rape of Belgium. by Mike Shuster. The Great War Project.

- ↑ The ‘German Atrocities’ of 1914. Sophie de Schaepdrijver. British Library.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Rape of Belgium.

- ↑ High Voltage Fence (The Netherlands and Belgium). By Alex Vanneste. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Wire of Death.

- ↑ Kossmann, E. H. (1978). The Low Countries, 1780–1940. Oxford History of Modern Europe (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822108-1. p. 533–4.

- ↑ Location of the 1914-1918 Battlefields of the Western Front. The Great War.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Post-war Economies (Belgium). International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Belgium: The Interwar period. Britannica.

- ↑ Léon Degrelle. Britannica.

- ↑ Richard Bonney. Confronting the Nazi War on Christianity: the Kulturkampf Newsletters, 1936–1939; International Academic Publishers; Bern; 2009 ISBN 978-3-03911-904-2; pp. 175–176

- ↑ Shirer, William L. (1990) [1960], The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7 p. 729

- ↑ Bond, Brian (1990), Britain, France, and Belgium, 1939–1940, London: Brassey's (UK) Riverside, N.J, ISBN 978-0-08-037700-1 p. 93.

- ↑ Knight, Thomas J. (March 1969). "Belgium Leaves the War, 1940". The Journal of Modern History. 41 (1): 52. doi:10.1086/240347. JSTOR 1876204. S2CID 144164673.

- ↑ Geller, Jay Howard (January 1999). "The Role of Military Administration in German-occupied Belgium, 1940–1944". Journal of Military History. 63 (1): 99–125. doi:10.2307/120335. JSTOR 120335.

- ↑ Jacquemyns, Guillaume; Struye, Paul (2002). La Belgique sous l'occupation allemande: 1940–1944. Brussels: Éd. Complexe. p. 307. ISBN 2-87027-940-X.

- ↑ Chiari, Bernhard; Echternkamp, Jörg; et al. (2010). Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg. 10. Munich: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. p. 669. ISBN 978-3-421-06528-5.

- ↑ Conway, Martin (2012-01-12). The Sorrows of Belgium: Liberation and Political Reconstruction, 1944–1947. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-0-19-969434-1.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Courcelles massacre.

- ↑ MacDonald, Charles (1984). A Time For Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34226-6.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Malmedy massacre.

- ↑ Allen, Robert W. (2003). Churchill's Guests: Britain and the Belgian Exiles during World War II. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. pp. 83–90. ISBN 978-0-313-32218-1.

- ↑ Willame, Jean-Claude (1972). Patrimonialism and political change in the Congo. Stanford: Stanford U.P. p. 62. ISBN 0-8047-0793-6.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Liberation of Belgium.

- ↑ Van den Wijngaert, Mark; Dujardin, Vincent (2006). "La Belgique sans Roi, 1940–1950". Nouvelle histoire de Belgique. Brussels: Éd. Complexe. ISBN 2-8048-0078-4. p. 27

- ↑ "Allies' dilemma over 'cowardice' of Belgian king". The Independent.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 "Belgian Royal Question" - the Abdication Crisis of King Leopold III of the Belgians. The Royal Articles.

- ↑ Belgian Colonial Education Policy. Ultimate History Project.

- ↑ Heart of Darkness: the Tragedy of the Congo, 1960-67. World At War.

- ↑ Belgian Congo. Britannica.

- ↑ The Congo, Decolonization, and the Cold War, 1960–1965. US State Department.

- ↑ Congo Civil War. Black Past.

- ↑ Belgium after WWII. Britannica.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Federalized Belgium. Britannica.

- ↑ North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) Kingdom of Belgium.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Benelux.

- ↑ Brussels. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Politics of Belgium.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Belgian Federal Parliament.

- ↑ Compulsory voting around the world. The Guardian.

- ↑ Belgium's ex-King Albert II admits fathering child after DNA test. BBC News.

- ↑ Belgian King meets with his once-secret half-sister for the first time, after years of legal wrangling. CNN.

- ↑ Belgium ex-king's love child seeks royal rights and titles. BBC News.

- ↑ The role of the monarchy. Belgium.be

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Structure of Belgium. Flemish Parliament.

- ↑ COVID-19 Is Pushing Belgium’s Messy Federal System to Its Limits. World Politics Review.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Berlaymont building.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Brussels and the European Union § European Quarter.

- ↑ Laconte, Pierre; Carola Hein (2008). Brussels: Perspectives on a European Capital. Brussels, Belgium: Foundation for the Urban Environment. ISBN 978-2-9600650-0-8.

- ↑ NATO Headquarters. NATO.

- ↑ New home, but same worries, as NATO moves into glass and steel HQ. Reuters.

- ↑ "Churchgoers in Brussels threatened with extinction" (in Dutch). Brusselnieuws.be. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ Kerken lopen zeer geleidelijk helemaal leeg – Dutch news article describing church attendance in Flanders. Standaard.be (2010-11-25). Retrieved on 26 September 2011.

- ↑ "CD&V stapt mee op gay-pride - CD&V marches along with gay pride" (in Dutch). Cdenv.be. 12 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ "In België wonen 650.000 moslims". Indymedia.be. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ "Vreemde afkomst 01/01/2012". Npdata.be. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ "Special Eurobarometer, biotechnology, page 204" (PDF). Fieldwork: Jan-Feb 2010.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 World Factbook: Belgium. CIA.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Belgium § Environment.

- ↑ Pilot 2006 Environmental Performance Index – Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy and Columbia University Center for International Earth Science Information Network